January 8, 2026 | Leslie Aquinde

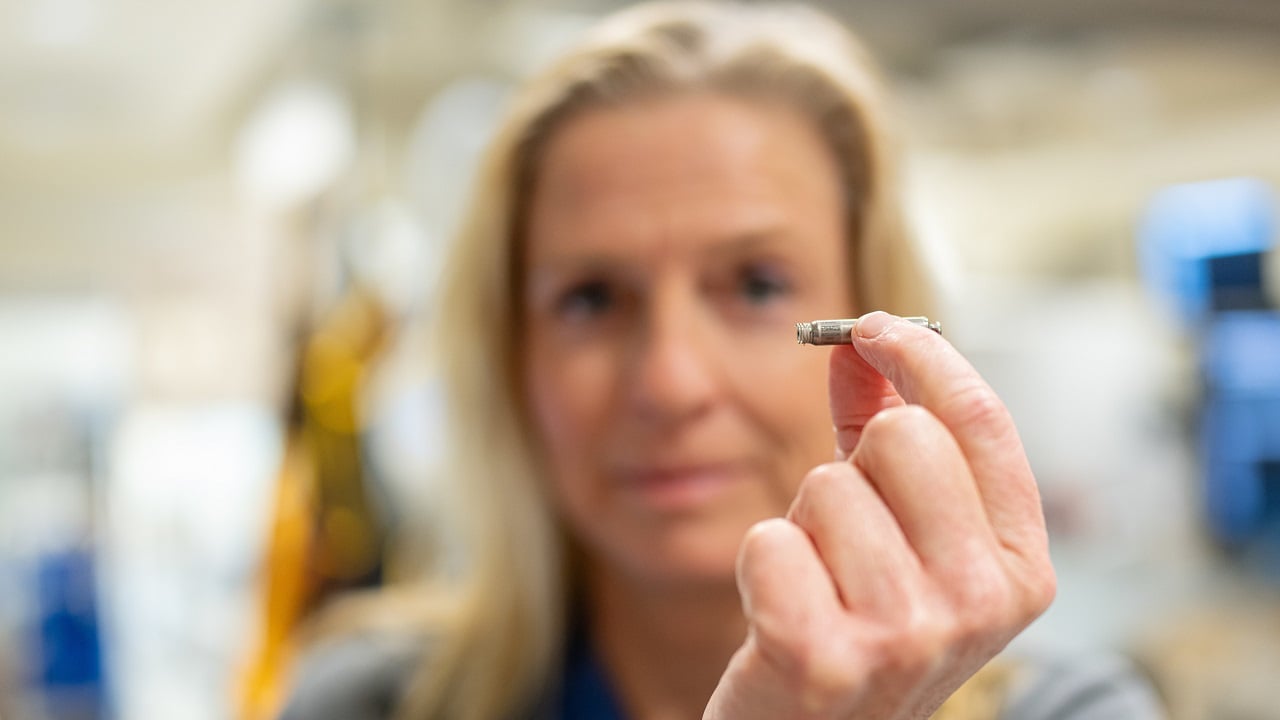

Personalizing Cancer Treatments Significantly Improve Outcome SuccessFirst global trial shows tumor DNA-guided cancer therapy is safe and effective, improving outcomes through personalized drug combinations in oncology care.